Half the Problem: What We’re Missing in Higher Ed

By Neal Modi | March 13, 2012 | Comments Off

Our current discourse on higher education focuses almost exclusively on access and affordability. How can we ensure that more students enter tertiary education and how can we guarantee students choose majors that can make our state and nation competitive are both questions that presently dominate higher education roundtables.

Indeed, Governor McDonnell’s Commission on Higher Education Reform focused specifically on the question of access. In a press release announcing the creation of the commission, the Governor wanted the commissioners to focus particularly on:

- education affordability,

- increasing the number of college-age Virginians enrolling in public colleges and universities,

- how to attract and prepare young people for STEM fields,

- crafting a sustainable funding model for public higher education, and

- how to make Virginia a leader in providing education opportunities to military personnel.

While certainly these are admirable goals and should maintain a central focus in our Commonwealth’s discussion about tertiary education, we should also place a concomitant focus on graduation and retention rates. In other words, it is one thing to make sure that all students have routes to higher education, but it is an altogether different thing, albeit a less attractive one, to discuss what is going on at our college campuses today.

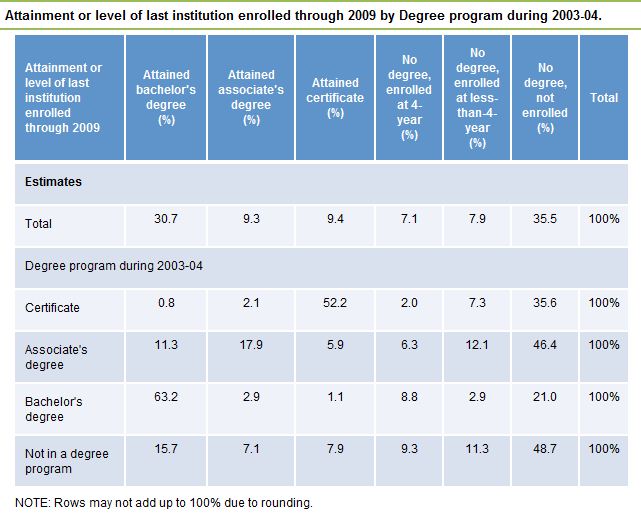

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), for all first-time college students enrolled in 2003, 30.7% earned a bachelor’s degree, 9.3% earned an associate’s degree, and 9.4% of students received a certificate by 2009, or in six years. At the same time, after six years, 15% were still enrolled somewhere in the higher education system, while 35.5%, more than the number of students who had graduated with a bachelor’s degree during that time, had dropped out.

But beyond these averages, there are even more troublesome disparities affecting our schools. In fact, they noticeably vary by student, degree, and institution type. For instance, according to the NCES, only 11.6% of students who begin their education at community colleges finish with a bachelor’s degree in six years (see table 1). At public four-year colleges and universities, the graduation rate is 59.5%, while at private, non-profit schools it is 64.6% and at for-profit schools, the graduation rate is a depressingly-low 15.7%. (Read about the threat of for-profit institutions here.)

Perhaps the most worrisome statistic is that the racial and socioeconomic gaps witnessed in K-12 education perpetuate themselves at our post-secondary schools. For example, according to the NCES, the nationwide graduation rate for white students beginning at four-year schools is 62.6%. For blacks, it is 40.5% and for Hispanic students, it is 41.5%. Additionally, while white students who began at two-year institutions have the same probability in attaining a certificate as blacks, they are 60% more probable to earn an associate’s degree, and are over two times more likely to receive a bachelor’s degree. Further, 47.1%, or less than half, of four-year students who come from backgrounds in the bottom income-quartile do not earn bachelor’s degrees on time, while 76.4%, or about three-quarters, of top-quartile students do.

While Virginia, with a state-wide graduation rate in 2009 of over 56%, is ahead the national average (in large part due to the quality of schools it has, which is one of the largest determinants in overall graduation rate), these statistics should force policy-makers to re-align and shift their attention.

In a hypothetical world, even if the State of Virginia could double the number of students entering higher education, the fact that many do not graduate at all, or on-time, compounded with the reality that those who do graduate come from a homogeneous background is troubling. It has critical consequences for opportunity in our state.

Accordingly, we need sound policy and innovative reforms to guarantee that whether a student will graduate after four years, or even six years, cannot be ascertained the moment they enter college. Graduation should not correlate with socioeconomic or racial background, nor should it even correlate significantly with the type of institution students begin in or attend.

I applaud the Governor’s and the Commission on Higher Education’s emphasis on seeing more students enter college, but I simultaneously find it disheartening that this commission, which is comprised of scholars and experts on the issue, cannot see that they are talking about half of the problem. The other half – making sure students graduate – is as, if not more, important.

Thus, we should focus on guidance and college counseling in all types of higher education institutions, particularly community colleges - places where students, especially black students, appear to be falling through the cracks. Simultaneously, we should create a new discourse on higher education about graduation and retention, as opposed to access. Getting the public and media to think about these issues will certainly, like the widespread commentary on access to higher ed that exists now, result in some changes.

—

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this post are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of members of the NDP Steering Committee.

Comments are closed.